|

|

For years, many of our Knowledge Workers and clients have thought of MG Taylor as a provider of processes that promote and unleash group genius in their organizations. The DesignShop® system accomplishes this aim, but the process cannot be successfully applied without the accompanying innovative physical environment that removes many of the blocks that stymie and attenuate other group process techniques. Structure wins. Traditional physical environments embody so many powerful cultural cues left over from the industrial age, that creativity and productivity emerge only at a terrible expense and consumption of individual energy. In such environments it's impossible to work smarter--one can only work harder. In several recent conversations with Knowledge Workers and clients, I have come to realize that our ValueWeb™ System commands only an obscure understanding of the basic philosophy and methods related to the creation and operation of our environments. This paper and several others that appear in this quarter's Journal of Transition Management should begin to correct this situation. To begin, I'll describe the phenomenon of the soul-body dichotomy in our culture and its influence upon the field of Architecture. The Soul-Body Dichotomy This prevalent paradigm makes it difficult for both clients and Knowledge Workers to understand that great and productive environments cannot be realized within the structure of such either/or thinking. Designers, builders and users whose philosophy and culture proceeds from the soul-body dichotomy believe that an environment can be tastefully executed, or it can be economical; it can function properly or it can be beautiful; it can be practical or it can support well-crafted processes. Either/or, but never both/and. Chances are that you, the reader, are mentally compiling a list from your own experiences that prove the actuality and power of the paradigm. Unfortunately, most of our design experiences were conducted as a series of choices, instead of a creative challenge of synthesis. Continued clinging to the paradigm provokes the ruination of our planet, renders our communities sterile and impotent, and sullies and impoverishes human dignity. Architecture is the expression of the culture that builds it. The proper accomplishment of all three attributes--Shelter, Arrangement and Expression--define the function of architecture. Nevertheless, the highest synthesis of these three can only emerge from a philosophy that does not see them as independent, hierarchical, or at war with one another. Rather, they are interdependent and support one another's proper execution. The healthy manifestation of architecture throughout history demonstrates this truth time and again. The Development of My Philosophy The concept of the three attributes of architecture (shelter, arrangement, and expression) is my “invention” that stems from my early years. What I was seeking to resolve with these formulations was the elimination of the deadly either/or thinking that always leads to compromise. When I began practicing architecture, function was defined as incorporating the utility and practical aspects of the work, and the art--if any--was tacked on as usually useless ornament.

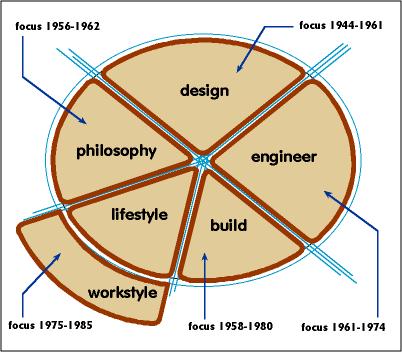

In the mid 70's I started to think of the information aspect of work-focused architecture and that led to the integration of environments, tools and processes and the development of Management Centers. This entire journey was one of searching for and incorporating those elements that are intrinsic to the basic nature of architecture and those which drive the design process. I added elements into my design process in this order:

The interesting thing is that as I added elements I became less and less employable. As my scope of understanding broadened across the design/build/use spectrum, I ceased to fit into any of the pigeon holes that comprise the industry. I was neither an architect, builder, engineer, nor user, but all of these at once. Still today architecture is not practiced from this level of synthesis, except for a sturdy community of architects who practice the best of residential design. What's missing from the industry is a design process that combines and releases the genius of a collaboration of practitioners who work with each other through the life span of the building or environment. The DesignShop process provides a model for such collaboration that is practical, inclusive, and dynamic enough to allow the practice of architecture in this way. Now we are assembling the ValueWeb ecology that requires and allows this way to be expressed and practiced. Our Knowledge Workers and clients must strive to understand through applied experience, the design/build/use model and the integration of tools, process and environment required to make it work. Related Articles: copyright © 1997, MG Taylor Corporation.

All rights reserved 19970427181202.web.bsc |

|

Copyright,

|

iteration

3.5

|

I started to think about the true economic aspects of architecture

as a builder in New York City in the early ‘60’s. Until that time, my

entire understanding of a project equated money, value and budget for

the design and construction phase of the life of the building. My sole

concern was getting enough budget to make the building ready for occupancy.

However, I began to glimpse the true measure of value and worth as stretching

over the life of the building; perhaps even over the life of future projects

that would be built on the same ground. My decisions were influencing

not only the design and the construction, but the considerably longer

timespan of the use of the building. And at that time, after the completion

of a structure, alterations to the design or the buildout were problematical

and expensive. There was no design/build/use cycle but only a design/build/use

straight line. The result of my thinking may be found in MG Taylor's

I started to think about the true economic aspects of architecture

as a builder in New York City in the early ‘60’s. Until that time, my

entire understanding of a project equated money, value and budget for

the design and construction phase of the life of the building. My sole

concern was getting enough budget to make the building ready for occupancy.

However, I began to glimpse the true measure of value and worth as stretching

over the life of the building; perhaps even over the life of future projects

that would be built on the same ground. My decisions were influencing

not only the design and the construction, but the considerably longer

timespan of the use of the building. And at that time, after the completion

of a structure, alterations to the design or the buildout were problematical

and expensive. There was no design/build/use cycle but only a design/build/use

straight line. The result of my thinking may be found in MG Taylor's