|

[Editor's Note: This article was inspired by comments made by Matt

Taylor during the 7 Domains® Workshop held in the Cambridge, MA, knOwhere

Store on August 25-28, 1997. The model for Communities of Practice was

developed by Bryan Coffman and Jay Smethurst.]

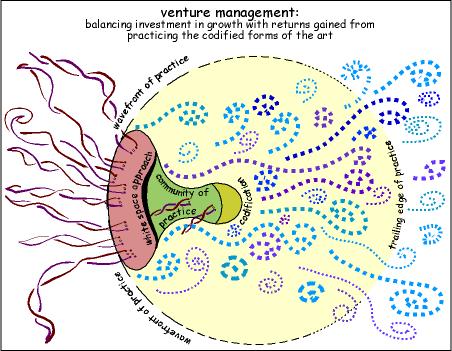

For any member of a Community of Practice, there comes a time to interface

with individuals and organizations which do not form part of the Community.

The difficulty of this situation is the issue of language. Every Community

of Practice--from physicists to painters to builders--has its own pattern

language, its own way of expressing and discussing the unique qualities

of its chosen art. This pattern language consists of the terms of art

of the practice, the models that the Community uses to express itself

and to translate reality, and the grammar that the Community uses to organize

the models and terms of art.

Think of a high school math class. As a rule, very little ground-breaking

work goes on in an Algebra or Calculus class. Innovation generally comes

later, once the "fundamentals" of math have been grasped, but

what do we mean by "fundamentals"? What a high school math course

teaches is the pattern language of the Community of Mathematicians. Algebra

teaches the rudimentary terms of the art--"function", "variable",

"equation". Geometry introduces some mathematical models--right

angles, planes, lines, points--and some of the grammar associated with

proofs--"if...then", causality, relationships. Calculus develops

all three elements of the pattern language--vocabulary, models, and grammar.

Now, the pattern language of mathematics is essential for practicing

the art of math. Certainly without this foundation, higher mathematics

would be inconceivable. What is missing from many high school math courses

is the reason for learning this pattern language--the passion and the

art. The pattern language is a valuable tool, but only if it is used to

achieve something. Occasionally, this indoctrination in the language of

mathematics will spark a passion in a student strong enough to make that

student a member in the Community of Mathematicians, but normally this

introduction to the art of mathematics passes as rudimentary understanding

into other Communities of Practice.

A Community of Practice does not exist outside of its membership, but

its essence is more than the mere sum of its members. A Community normally

forms around an art, a discipline, and it is the passion for that art

that creates the loyalty and the organization. Of course, members drawn

to the Community of Practice will be attracted for very personal reasons,

and will each have a different perspective on the nature of the art that

they are practicing. These different understandings will lead to a diversity

of forms and practices which will lead inevitably to controversy. It is

this controversy that must be both nurtured and resolved.

Practitioners of an art must push its limits. Art is exploration, and

to do simply what is already known is to kill both the art and the artist.

An artist must reach into the unknown, must draw from other arts to enhance

his own. Outside of the known is the void, the "white space"

from which all inspiration comes. (See the Benjamin

Hoff quote from 1997/07/27.) As individual artists reach out in their

own ways into the white space, they both make it known and bring themselves

into the unknown. In so doing (so long as they do not break entirely away

from the Community), they pull the Community of Practice along with them.

As they venture forward, they (or their work) must engage the Community

as a whole in a dialogue, exploring and explaining the white space in

consideration.

Now as the artist returns from the exploration of the white space to

the Community, he must use the language of the Community--the pattern

language--to explain, demonstrate, defend, or otherwise elucidate his

discoveries. In mathematics, the explorer must defend her discoveries

using proofs based on accepted theorems, axioms and other proofs. An architect

must justify his work through forms, function and materials. A gardener

must be able to explain and justify any exploration in terms of arrangement,

soil, minerals, water, weather and a multitude of other factors that constitute

the pattern language of the art of gardening.

As artists push the Community into new territory, the "old"

territory becomes comfortable and safe. The forms and earlier explorations

become part of the pattern language, change the shape of the models of

the Community and eventually become codified in such a way that they can

be readily understood by a novice or a lay person. Take as an example

the Copernican notion that the Earth revolves around the sun. It was revolutionary

and terrifying at the time it was proposed, yet since it was defended

by "proper" scientific method, it became acceptable. And as

it became acceptable, it became part of the pattern language of cosmology

and other learnings began using this model as a foundation from which

to make further assumptions. As this happened, the further assumptions

became terrifying to the lay person and the Copernican model became commonplace--so

commonplace, in fact, that it was no longer of any particular interest

to those on the cutting edge of the discipline.

Nevertheless, as new ideas in one Community of Practice are accepted

within the Community and codified, they can be passed on to the general

public for easy consumption and possible application to other fields.

It is in passing on the codified idea, when non-practitioners find value

in its codified ideas and practices, that a Community of Practice can

generate return on their investments in exploration. The groundbreakers

in the field of complexity theory, like the Santa

Fe Institute, were ignored as marginal and irrelevant until businesses,

economists, and other industries began discovering possible value in the

work that complexity theorists were doing. Our recent 7

Domains® Workshop, for example, represents an attempt by lay folk

to apply the trailing edges of complexity theory to an entirely different

discipline.

Communities of Practice exist as their pattern language. This language

must be robust enough to express the depth and breadth of the art form,

and malleable enough to accomodate change and debate inside the discipline

itself. This language must also be coherent enough to allow itself to

be codified and translated to other Communities of Practice to be used

and adapted to suit their particular needs and visions. All Communities

seek to explore the white space. It is their method of exploration and

their means of communicating their experiences of exploration that differ.

copyright © 1997, MG Taylor Corporation.

All rights reserved

copyrights,

terms and conditions

19970924235718.web.jbs

|