|

Modeling Language Spotlight

Three

Cat

March 16, 1997 |

Editor's Note: This model is easily the most profound and

esoteric model in the entire modeling language. Its philosophical implications,

implied by its feedback loops, challenge our current world view of how the universe

works. This article, however keeps to the level of playing with the simpler

ramifications of the model, leaving the larger questions for another time...

Like the other models of the MG Taylor Modeling Language,

the Three Cat Model is protected by copyright. You can use it only by meeting

these four conditions.

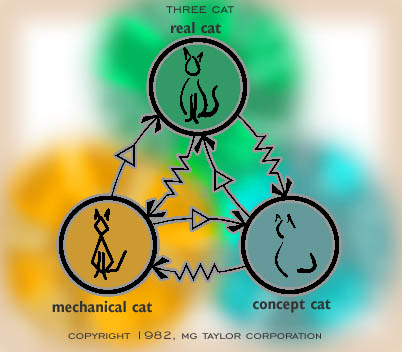

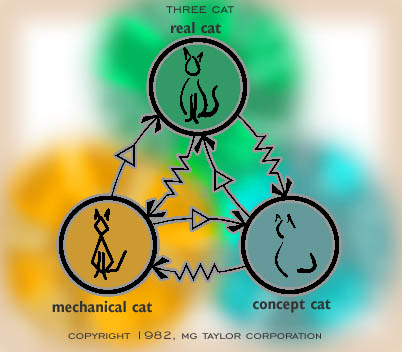

The Basic Model

The Three Cat model is a metaphor for information management in the act of creation.

It may be easily played in a glass bead game with any number of other models,

particularly the Seven Stages of the Creative Process.

On the simplest level, the model summarizes the acts of observing reality,

forming a concept, and testing that concept by building a model to reveal our

understanding. The model is then compared to reality for verification, the concept

is adjusted, the model rebuilt, and so on.

Here are the definitions of the three components of the model.

Now, what about the connections between the

three cats? There are two lines that connect any two cats. One line is a squiggle

and the other has a triangle in the middle of it. The squiggle is the symbol

for a resistor in electronics and refers to the attenuation of information traveling

in that direction. So, for instance, the communication of information from Real

Cat to Concept Cat is severely attenuated. The triangle is another symbol borrowed

from electronics--an amplifier. The information running from Concept Cat back

up to Real Cat is amplified. You don't have to be an electrical engineer, however,

to understand what's going on. Imagine that you're an artist about to draw a

cat. When you look at the cat, do you transfer everything there is to see about

the cat into your mental concept? No. In fact, you throw away nearly all of

the potential information that you can perceive--99% is a conservative estimate.

Instead, you concentrate on the way the back curves or the spacing and shape

of the eyes. Even when the painting is done, and even if it's done in a photographic

style, you will have only captured a tiny fraction of all that is there to be

seen. The point of art--whether its painting or the art of managing an enterprise--is

to be aware of what you're choosing to keep, and what you're throwing away.

Then the challenge is to shape what's left into a whole that conveys whatever

message you wish. Now, what about the connections between the

three cats? There are two lines that connect any two cats. One line is a squiggle

and the other has a triangle in the middle of it. The squiggle is the symbol

for a resistor in electronics and refers to the attenuation of information traveling

in that direction. So, for instance, the communication of information from Real

Cat to Concept Cat is severely attenuated. The triangle is another symbol borrowed

from electronics--an amplifier. The information running from Concept Cat back

up to Real Cat is amplified. You don't have to be an electrical engineer, however,

to understand what's going on. Imagine that you're an artist about to draw a

cat. When you look at the cat, do you transfer everything there is to see about

the cat into your mental concept? No. In fact, you throw away nearly all of

the potential information that you can perceive--99% is a conservative estimate.

Instead, you concentrate on the way the back curves or the spacing and shape

of the eyes. Even when the painting is done, and even if it's done in a photographic

style, you will have only captured a tiny fraction of all that is there to be

seen. The point of art--whether its painting or the art of managing an enterprise--is

to be aware of what you're choosing to keep, and what you're throwing away.

Then the challenge is to shape what's left into a whole that conveys whatever

message you wish.

But what about the amplification in the model? Take a look at

the amplification line leading from Mechanical Cat back to Real Cat. Imagine

that you've drawn a line on your paper that represents the curve of the cat's

back. Someone happens to walk by, and glancing at your drawing in progress asks,

"what's that?" You explain that the line represents the curve of the

cat's back. Your explanation is an amplification of the mechanical drawing you've

done, so that it can be properly related to the reality is represents. In business,

spreadsheets are accompanied by memos explaining various terms and abbreviations

(not to mention the results). All mechanicals--all physical or tangible models

require explanation when they are related back to the reality they represent.

Sometimes the explanation is built into the culture and remains hidden, other

times it must be more clearly stated.

Summary of the Connections

Real Cat-Concept Cat

ATTENUATION

This has been covered in the discussion above. Information flowing from reality

is severely attenuated as it takes shape in our mental models. The methodology

used for determining what to throw away and what to keep is addressed in the

'Spoze model.

AMPLIFICATION

This is usually an unconscious act. Our concept of cat, for example,

probably includes only a few basic features--the ones most everyone can draw--the

triangular ears, curve of the mouth, the oval pupils. We don't need to "download"

all information about all cats in the universe to build a good enough mental

model that lets us distinguish cats from other kinds of animals. In order to

learn more about cats, however, we must translate our mental symbology back

up to reality by amplification. Here's an example.

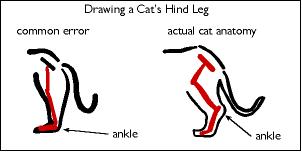

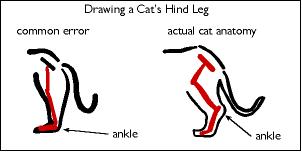

Many people don't realize that cats don't walk on their hind feet. Instead,

they walk on their toes. What we think is the cat's leg extending below it's

body is mostly foot, ankle and lower leg. The upper leg is hidden in the mass

of the animal's body. In order to correct this deficiency of understanding,

most people must consciously amplify the simple stick leg they are used to drawing

to represent the cat's back leg and begin to compare it with what's really going

on in the cat's anatomy. Instead, many inexperienced artists get caught drawing

and redrawing the same mistakes because they are unaware of the mismatch between

their concept and the reality. Even looking at the real cat doesn't seem to

help. Their concept must be revealed or made plain and amplified in the mind

of the student before the mistake can be realized and corrected. Many people don't realize that cats don't walk on their hind feet. Instead,

they walk on their toes. What we think is the cat's leg extending below it's

body is mostly foot, ankle and lower leg. The upper leg is hidden in the mass

of the animal's body. In order to correct this deficiency of understanding,

most people must consciously amplify the simple stick leg they are used to drawing

to represent the cat's back leg and begin to compare it with what's really going

on in the cat's anatomy. Instead, many inexperienced artists get caught drawing

and redrawing the same mistakes because they are unaware of the mismatch between

their concept and the reality. Even looking at the real cat doesn't seem to

help. Their concept must be revealed or made plain and amplified in the mind

of the student before the mistake can be realized and corrected.

Concept Cat-Mechanical Cat

ATTENUATION

Despite the limited scope of our concepts, they are vastly more complex than

the models we can make from them. No matter how hard we try, no tangible model

that we make ever exhibits all of the features that we can imagine incorporating.

At some point we have to stop. Knowing what to leave in and what to throw out

is most of the game.

AMPLIFICATION

Our models nearly always require explanation. We find ourselves

constantly reminding ourselves that "the number in this cell corresponds

to this feature". Documentation and technical journals are created to correct

this problem, but really the only answer for it is collaboration among designers.

Mechanical Cat-Real Cat

ATTENUATION

The purpose of building a model is not to replicate reality. We've already seen

that the laws of successive attenuation in the model prohibit such a purpose

from succeeding. Therefore, it is useless to require such impossible fidelity.

The characteristics and infinite detail of the Real Cat are captured only in

aggregate by the model. Nevertheless, it is possible for the model to prove

its fidelity with Real Cat behavior at this aggregate level. For example, we

might expect a painting to present us with the essence of a real cat, but not

the behavior of the cat over time. The artist chose a static medium to prove

her concept. There' s no point in asking why it doesn't show the cat in the

process of running. Likewise, business models will be based upon a great many

assumptions of the aggregate behavior of components of the real business, or,

in the case of agent-based emergent systems simulations, on assumptions for

the rules of behavior of individual agents in the enterprise.

AMPLIFICATION

This was discussed in the text above. Because our models are

comprised of so much less information than was contained in either the Real

Cat or the Concept Cat, some portions of the model will probably have to be

translated, and portions of the reality will be missing entirely. These omissions

often require explanations.

The Uses and Abuses of Two-Catting

The model works great when it's employed with attention, craft and discipline.

There are some practices that must be watched for and employed with care: they

have the potential for both great value and danger. These occur most often when

one of the cats is removed from the iterative process. Because there are three

cats in the model, there are three possible combinations of two-catting. I'll

look at them in turn.

Real Cat-Concept Cat Real Cat-Concept Cat

GREATEST VALUE

Often we need to learn the art of observation. In business it may take the form

of "management by walking around." Sometimes our lack of skill in

building mechanical models hampers our ability to translate features from the

Real Cat down into our concept. In these cases, some focused interaction between

only your mental concept of something and the object itself can help establish

a good mental model. This is also a way to develop "gut feelings"

that can tend to pan out well in certain circumstances.

GREATEST DANGER

This kind of two-catting allows all sorts of unsubstantiated assumptions and

errors to accumulate. A non-geologist can look at an outcrop of rock and develop

some mental model about how it got to be the way it is, but the concept will

likely be based on incorrect assumptions. Since the observer is under no obligation

to prove the model by putting the assumptions on paper and then testing them

against a different outcrop, there's little chance of ever being set straight.

Concept Cat-Mechanical

Cat Concept Cat-Mechanical

Cat

GREATEST VALUE

Sometimes it's good to just do a core dump and tweak a model. Sometimes it's

too expensive to return to the "real cat" over and over again to improve

the concept, and data must be collected in the initial stages, brought back

from the field, and worked into a model in isolation of the thing being modeled.

[Note that if the data is collected physically, then that represents building

a mechanical cat.] This is also a great tool for building a working model of

your assumptions. Such a model can be used diagnostically to discover any holes,

inconsistencies or errors in your concept.

GREATEST DANGER

Without any reference to reality, it's easy to build up a sort of nonsense,

fantasy world. In extreme cases, it's possible to believe that the Concept Cat

IS the Real Cat. We all suffer this at one time or another, and it plagues civilization

in general. Stereotypes, prejudices, a sense of personal limitation, and fear

all result from this closed loop behavior between what we think the world is

like and our documentation of these personal beliefs. Pseudoscience falls in

this category of two-catting.

Mechanical

Cat-Real Cat Mechanical

Cat-Real Cat

GREATEST VALUE

Once we believe something about reality--once we have a firmly established concept

or mental model--it can be very hard to uproot and change. Eliminating Concept

Cat from the equation can be useful in these circumstances. But it's difficult.

One technique is suspending judgment when testing a model with reality--especially

a priori judgment.

GREATEST DANGER

Without engaging Concept Cat, we don't learn. Many of us have had jobs that

required only a mindless comparison of figures on reports (Mechanical Cat) to

items in an inventory (Real Cat). No thinking involved. No growth potential.

copyright © 1997, MG Taylor Corporation.

All rights reserved

copyrights,

terms and conditions

19970316235847.web.bsc

|

Now, what about the connections between the

three cats? There are two lines that connect any two cats. One line is a squiggle

and the other has a triangle in the middle of it. The squiggle is the symbol

for a resistor in electronics and refers to the attenuation of information traveling

in that direction. So, for instance, the communication of information from Real

Cat to Concept Cat is severely attenuated. The triangle is another symbol borrowed

from electronics--an amplifier. The information running from Concept Cat back

up to Real Cat is amplified. You don't have to be an electrical engineer, however,

to understand what's going on. Imagine that you're an artist about to draw a

cat. When you look at the cat, do you transfer everything there is to see about

the cat into your mental concept? No. In fact, you throw away nearly all of

the potential information that you can perceive--99% is a conservative estimate.

Instead, you concentrate on the way the back curves or the spacing and shape

of the eyes. Even when the painting is done, and even if it's done in a photographic

style, you will have only captured a tiny fraction of all that is there to be

seen. The point of art--whether its painting or the art of managing an enterprise--is

to be aware of what you're choosing to keep, and what you're throwing away.

Then the challenge is to shape what's left into a whole that conveys whatever

message you wish.

Now, what about the connections between the

three cats? There are two lines that connect any two cats. One line is a squiggle

and the other has a triangle in the middle of it. The squiggle is the symbol

for a resistor in electronics and refers to the attenuation of information traveling

in that direction. So, for instance, the communication of information from Real

Cat to Concept Cat is severely attenuated. The triangle is another symbol borrowed

from electronics--an amplifier. The information running from Concept Cat back

up to Real Cat is amplified. You don't have to be an electrical engineer, however,

to understand what's going on. Imagine that you're an artist about to draw a

cat. When you look at the cat, do you transfer everything there is to see about

the cat into your mental concept? No. In fact, you throw away nearly all of

the potential information that you can perceive--99% is a conservative estimate.

Instead, you concentrate on the way the back curves or the spacing and shape

of the eyes. Even when the painting is done, and even if it's done in a photographic

style, you will have only captured a tiny fraction of all that is there to be

seen. The point of art--whether its painting or the art of managing an enterprise--is

to be aware of what you're choosing to keep, and what you're throwing away.

Then the challenge is to shape what's left into a whole that conveys whatever

message you wish. Many people don't realize that cats don't walk on their hind feet. Instead,

they walk on their toes. What we think is the cat's leg extending below it's

body is mostly foot, ankle and lower leg. The upper leg is hidden in the mass

of the animal's body. In order to correct this deficiency of understanding,

most people must consciously amplify the simple stick leg they are used to drawing

to represent the cat's back leg and begin to compare it with what's really going

on in the cat's anatomy. Instead, many inexperienced artists get caught drawing

and redrawing the same mistakes because they are unaware of the mismatch between

their concept and the reality. Even looking at the real cat doesn't seem to

help. Their concept must be revealed or made plain and amplified in the mind

of the student before the mistake can be realized and corrected.

Many people don't realize that cats don't walk on their hind feet. Instead,

they walk on their toes. What we think is the cat's leg extending below it's

body is mostly foot, ankle and lower leg. The upper leg is hidden in the mass

of the animal's body. In order to correct this deficiency of understanding,

most people must consciously amplify the simple stick leg they are used to drawing

to represent the cat's back leg and begin to compare it with what's really going

on in the cat's anatomy. Instead, many inexperienced artists get caught drawing

and redrawing the same mistakes because they are unaware of the mismatch between

their concept and the reality. Even looking at the real cat doesn't seem to

help. Their concept must be revealed or made plain and amplified in the mind

of the student before the mistake can be realized and corrected. Real Cat-Concept Cat

Real Cat-Concept Cat Concept Cat-Mechanical

Cat

Concept Cat-Mechanical

Cat Mechanical

Cat-Real Cat

Mechanical

Cat-Real Cat