|

|

|

Modeling Language Spotlight

Creating

the Problem

July 4, 1997 |

Like the other models of the MG Taylor® Modeling

Language, the Creating the Problem Model is protected by copyright.

You can use it only by meeting these

four conditions.

How many times have you found yourself fully

immersed in a project, only to discover that the real problem lies elsewhere

and that you are treating only a symptom? Too often we attack what we perceive

to be problems without considering the bigger picture. Too often we spend tremendous

resources in energy and money to duplicate the work of others, simply because

we did not take the time to discover if others could help us. Too often we go

into a project assuming that the whole team shares a vision, only to realize

later that we had very little common understanding to begin with. These kinds

of situations underscore the need, before all else, to create the problem that

you are trying to solve.

| glyph info |

Element |

Description |

|

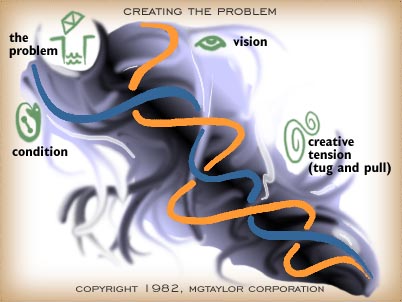

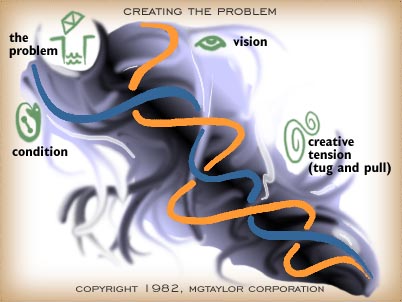

Condition . |

These are the existing conditions before you begin the creative process.

Notice that these conditions, in and of themselves, are merely conditions.

They are not the problem. These conditions are in constant flux and

will change as the creative process advances |

|

Vision |

This is your vision for an ideal future state. In creating this vision,

take into account your personal experiences, insights and views of reality. |

|

Problem |

The problem is created when you discover a gap between reality and

your vision for a new reality. The problem is neither current conditions

nor the vision. Rather, it is the discrepancy between them. |

|

Creative Tension |

The creative tension that comes into being when you decide to resolve

the problem is the interplay between vision and reality. As the two

tug and pull at each other, they will each change and modify in an effort

to reach a synthesis. |

Creating the Problem

If your neighbor Jim were to tell you, "I can't read," he would be

stating a condition, not a problem. The condition exists. There is nothing either

good or bad about not being able to read. In fact questions of value are irrelevant,

for the condition is neutral. Jim cannot read, and that statement holds no meaning

other than the condition it states.

[Our immediate response to this idea is "No! Not being

able to read IS a problem!" Let us step back for a moment. We have no problem

with the idea that "The wall is white," is simply a statement of a

condition. "It is 10 o'clock," is also a condition. These conditions

simply exist and they are completely neutral. It is only when we bring a vision

to those conditions, a vision that is DIFFERENT from those conditions, that

a problem is created. "The wall is white, but I want it to be green."

Now there is a problem to solve. "It is 10 o'clock, but I was supposed

to be at work at 9." Now you have a problem. Many times we encounter a

condition and unconsciously apply a vision to it to create a problem. We therefore

assume that the condition IS the problem. "My shoe is untied." We

assume that that is a problem. In fact it is just a condition. It only becomes

a problem if we are walking around in that shoe and we don't want to trip over

the shoelace. Now we have created a problem. (If the shoe is in the closet and

is untied, then we expect it to be untied--the vision matches the conditions--and

we have no problem.) "Jim cannot read," is only a condition. "Cats

can't read," is also a condition. We don't expect cats to read so we do

not create a problem there. It is only because we EXPECT (have a vision) Jim

to read, that we create a problem around it. "Jim should be able to read,

but he can't." That is a problem. "Jim can't read," is a factual,

neutral condition against which no vision has been juxtaposed. Jim's not reading,

in and of itself, is therefore not a problem.]

Jim continues, "I want to be able to read street signs. I

want to be able to read stories to my children at night. I want to read the

newspaper. I want to write the great American novel." Each of these statements

expresses a vision, and now that Jim has a vision that differs from his current

conditions, he has created a problem. The problem is a recognition that your

vision does not match the current conditions.

Simply because a problem exists, however, does not mean that Jim will do anything

about it. When he decides to resolve the discrepancy, the the distance between

vision and conditions becomes a creative tension that will drive his creative

process to resolution. That gap will work to close itself. In fact the distance

between vision and conditions can be seen as potential energy that, as the creative

process brings vision and conditions closer together, transforms into kinetic

energy, driving the process with more and more momentum as it nears completion.

With that analogy in mind, it becomes quite obvious that a limited vision, one

that differs very little from the current conditions, will have very little

potential energy to begin with and will therefore never get much creative kinetic

energy. A more drastic vision, on the other hand, one that differs tremendously

from current conditions, will have tremendous potential and kinetic energy.

If Jim limited his vision to wanting to read street signs, then he would have

very little creative tension. He may have to work very hard to learn to read

street signs, and once he could do that, then he might very well stop his learning

process. If on the other hand, he decided that he wanted to write the great

American novel, then he would have set up tremendous creative tension. He might

very well start his learning slowly, on something like street signs. Then he

would learn to read simple stories, like ones he might read to his children.

He might then advance to reading newspapers as he began writing short stories

and maybe even poetry to learn how words can interact in different ways. During

this process, current conditions are changing. They are spiraling faster and

faster towards Jim's vision, just as Jim's vision is coming closer to his conditions.

Finally, once he had written the great American novel, Jim would have accomplished

all sorts of other things that he had wanted to do. Since he had done them in

the context of a larger vision, however, they had not taken nearly as much effort

as if they had been singular, limited creative processes--each requiring his

own energy to start them up and not capitalizing on the momentum created by

the more visionary approach. Vision and conditions are now one, and there no

longer exists a creative tension. Conditions have changed and now there can

be a new vision created to differ from these new conditions. Jim might now want

to win a Pulitzer Prize--a remotely viable goal, now that Jim can read and write

whereas before, a Pulitzer would have been beyond comprehension.

This first part of the example has demonstrated the importance of setting a

proper vision, but what about sharing the vision? Jim has told you that he can't

read. Now let's assume that he tells you that he wants to read the instruction

manual for his new TV. What he does not tell you, because he's a little embarrassed,

is that he really wants to learn to write love poetry for his wife. When you

agree to teach him to read, you expect everything to go well, but Jim becomes

distracted, frustrated and disengaged. He is not learning what he wants to learn,

but you cannot know that because he hasn't shared his vision with you. This

disjoints the entire creative process because the two people involved have created

two different problems.

This problem compounds itself if you find a whole group of people whose vision

is to read. What do they want to read? Why do they want to read? Some will want

to read street signs. Others will want to write poetry. Still others will want

to write letters. Others may want to write novels. Everyone's vision will be

different, and if you attempt to teach at this point, you and they will all

become frustrated. You will be disjointed and distracted since you are trying

to teach each person what she wants to know. The learners will become frustrated

because they are not being taught what they want to know. What the group needs

to do is to create a common vision. Each person must figure out what elements

of their personal vision are important and which elements are flexible. Would

the street sign people be willing to learn how to write poetry? Would the novelists

be willing to start with poetry? By creating a vision that includes and adds

to the essential elements of each individual's vision, the group can create

a collective problem that it can be united in solving.

And lastly, what ARE the current conditions? Jim asks you to teach him and you

agree. Little does Jim know, however, that you cannot read either! So here the

two of you are, fumbling around with books and letters and words, spending a

great deal of energy but getting nowhere. Only after this fumbling around will

Jim discover that you don't read either, and after much time and energy is spent,

you finally get down to creating the right problem using the proper set of conditions:

neither one of you reads and you both want to write the great American novel.

This model highlights a number of factors that are important to consider when

you go about creating problems for yourself. First, current conditions are NOT

problems. Second, the difference between your vision and current conditions

(not the opposite--the "practicality" of your vision) drives the creative

process so do not temper your vision with reason--create what you really want

to create. Third, share your vision, choose the important elements, and work

to create a common vision that incorporates and adds to the personal visions

of the entire group. And lastly, be very clear about what the current conditions

are. There is no reason to deceive yourself here. Current conditions are what

they are, not what you or others would like them to be. By rigorously creating

the problem before you begin a creative process, you will clearly define the

parameters of your work and will drastically increase your chances of success.

Think back to projects that you have been involved with, whether individual

or group projects, that have failed or have taken much more time and effort

than they should have. How many of the difficulties you encountered involved

an unclear vision or misunderstood conditions? How many projects had a vision

that was actually very similar to the conditions that already existed? This

model attempts to avert these kinds of difficulties by clarifying the parts

of the creative process that are often left unspoken.

|

Journal Assignment: We have spoken

in this discussion about parameters and scope of vision. The Creating

the Problem model is an attempt to create appropriate solutions to problems

by rigorously defining the problem at the outset. The Appropriate Response

model speaks to solutions as well. Where and how does the Appropriate

Response model fit into the Creating the Problem model? For example,

where in the Creating the Problem model is there opportunity to measure

the appropriateness of the solution generated by the pull and tug of

the creative tension? |

copyright © 1997, MG Taylor Corporation.

All rights reserved

copyrights,

terms and conditions

19970704162144.web.jbs

|